I'm a busy man. Last year I received a work promotion, and when I'm not working, I'm wearing perfumes and publishing reviews on

Oh, and also putting energy into my relationship, and ensuring I find some time to dip in and check on my family. Finding five or six hours to sit down and read a book is extraordinarily difficult. But I was lucky to have a bit of spare time this week, and figured I was overdue to read Gabe Oppenheim's 2021 book, so I went cover-to-cover with it yesterday. Here are my thoughts.

I'll start with the good stuff first, and go from there. The good stuff: my favorite thing about this book are the circumstances under which it was written. Oppenheim was exclusively a sports writer prior to delving into the topic of perfumery, and from his own telling in interviews and in the book itself, it sounds like the pandemic helped to make his project possible. Being trapped indoors for months on end spurred him to explore the addictive world of fine fragrance, and it paid off. I appreciate that he ventured beyond his comfort zone and attempted to penetrate the inner workings of the perfume industry, and I'm also impressed that he could develop a rapport with high-profile people like Raymond Chaillan, Jean-Christophe Herault, Laurice Rahmé, and not least of all, Pierre Bourdon.

I like how the book pinpoints a specific crack in Olivier Creed's meticulous façade, which might be evidence that he falsified his family's entire perfume legacy. Oppenheim casually details how Bourdon lost to Edouard Fléchier an early eighties brief for L'Oréal's Courrèges in Blue. Bourdon's rejected submission was then "bought" by Olivier Creed, and became Fleurs de Bulgarie. This is notable because Fleurs de Bulgarie is one of Creed's supposedly historical perfumes, cited by the brand as having been originally created in 1845 as a bespoke for Queen Victoria, "under whose reign Creed served as an official supplier to the royal court." It is a clear case of an overlooked formula that our notorious perfume swindler sneakily appropriated and claimed had been made by one of his forefathers, when in fact it is as modern as a microwave oven.

Unfortunately, that's about all the good stuff I could find here. The rest was, well, underwhelming, to say the least. I'll get the petty stuff out of the way: on a grammatical level, the book is horribly written. It reads like a first draft that has been given a cursory once-over. Oppenheim's prose is rife with spelling, punctuation, and grammatical errors, including several ridiculous hypotactic sentences. Take this one, for example:

"And if he confused the two accounts, so that members of the latter were often held to the severe standards he helped set in the former, well, that was to both the great fortune and detriment of his little boy, who'd come to understand young just what was considered an artistic contribution worthy of Dior's imprimatur -- and all the brilliant work that, for any number of reasons never shared, either with the boy regarding his homework or perfumer-aspirants their trials, was not." (chapter 4, page 42, Kindle edition)

He also has an unruly habit of deviating from an interesting subject, sometimes mid-paragraph, to an uninteresting one, and I often found myself wondering if I'd purchased the wrong book. In the final third of his narrative, he goes from talking about Olivier Creed (interesting), to talking about everyone else in the industry (uninteresting), from Coco Chanel, to Estee Lauder, to Roja Dove, to Pierre Montale, where he goes into unnecessarily elaborate detail about the many hidden legal problems that plagued the Montale brand. None of this was interesting, because it had nothing to do with Olivier Creed, or Pierre Bourdon. Obviously a book about perfume will digress to elucidate the milieu of the main players, but Oppenheim's concludes with his big meeting with Bourdon, and his lengthy Montale digression was so close to those final pages that I feared it was camouflage, or perhaps filler, for something anticlimactic.

My fears were well-founded; Oppenheim's day with Bourdon was uneventful, and he failed to illustrate any deep conversations that were shared with the master perfumer. Instead, he merely describes Bourdon's castle and interior design aesthetic, his paintings, his wife's fashion choices, a near-miss with orange juice and a fancy rug, and an emotional moment in the backyard after Bourdon awkwardly asks the author if he's Jewish. This is conveyed as a bonding moment, which might have resonated, except that earlier the young American had tried to brown nose his elder host, and received the coldest of snubs. Bourdon simply shrugged and turned away from Oppenheim to engage with Givaudan perfumer Shyamala Maisondieu, whom he no doubt was far more interested in. To me, this indicated an end to Bourdon's interest in conversing further. There is no formal interview with him, no direct questions and answers regarding his storied career, no firsthand accounts of his relationship with Olivier Creed, which I feel would have been quite stirring.

Oppenheim peppers throughout the book what useful information Bourdon offered him, but suggests it was acquired via email correspondences with Kathy, the Frenchman's half-British wife. The whole crux of the narrative is that Pierre, son of Rene Bourdon, the general manager of product development at Christian Dior, desperately wanted to follow in daddy's footsteps, but he was disapproving and hard to love. Young Pierre then ventured into the industry under the tutelage of the legendary Edmond Roudnitska, and proceeded to pursue his vocation at the esteemed "oil house," Roure. For some unknown reason, Oppenheim describes the budding perfumer's sexual escapades in borderline-lurid detail, including an unnecessarily vivid depiction of when he lost his virginity. I sensed that this was the author's way of signaling to the reader that Pierre had trusted him and confided in him, but it comes across as pointless and a bit underhanded.

The story follows the arch of Pierre's career, his separation and eventual divorce from his first wife, his time in New York and New Jersey, and the moments leading up to his creation of Dolce Vita with Maurice Roger. Oppenheim interprets Bourdon's path as an agonized estrangement, both from his wife and Roure, and it is repeatedly suggested that he would have been better off had he remained with both. It is also implied in elliptical language that Bourdon's ego is fragile, and that the many frustrations of his failed briefs, particularly the eight rejections of his formula for Cool Water, followed him into retirement. The problem I had with all of this is that it seemed to come entirely from Oppenheim, not Bourdon. While the history lessons were interesting enough, and the Bourdon narratives were consistently amplified, their provenance was suspect.

I found the way in which Oppenheim tied Bourdon's trajectory to Olivier Creed's to be even less satisfying. A major problem the author had here was that nobody in the Creed family would speak with him. Olivier and Erwin both spurned requests for interviews, and there were descriptions of uncomfortable exchanges with folks in their close orbit. The company briefly flirted with a direct interaction on behalf of Oppenheim's book, only to abruptly withdraw without explanation. This left the author to speculate that the nature of his project would conflict with a far less controversial self-promotional coffee table book the business had in the works. I found this to be pathetic, because the reason was far simpler, and worse, it was dead obvious: Creed knew Oppenheim had already framed their enterprise as fraudulent. Why on Earth would they ever engage with him?

This fact, which seems to have eluded the author, speaks to the folly of harboring forgone conclusions at the outset of a "journalism" project. Oppenheim put the cart before the horse here. Before he had written a single word, his view was that the Creeds had been spinning a complex web of lies about themselves, and his ensuing correspondences with industry insiders were attempts to validate it. Clearly, word got around. Worse still, instead of finding his "smoking gun," he uncovers some dead-ends that are incompatible with his hypothesis, which he admits are baffling. I could literally smell the cognitive dissonance wafting up from the pages as I read about these facts, and it smelled pretty foul. I had to inhabit Oppenheim's mentality to fully comprehend where he thought he could go here, and it turned out there were almost no avenues of enlightenment available to him.

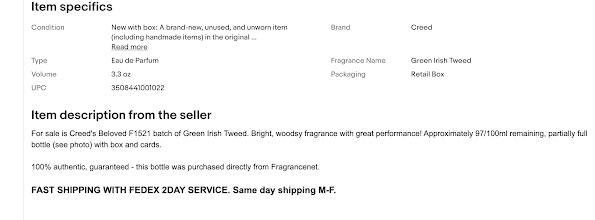

Bourdon and Creed intersect with Olivier pilfering each failed brief that the budding perfumer finds himself burdened with, starting with the formula for Courrèges in Blue (Fleurs de Bulgarie), then moving on to Lancôme's Sagamore (Green Irish Tweed), Erolfa (Bourdon can't remember what that one was originally for), Imperial Millesime (unclear if that was ever for anyone but Olivier), L'Eau d'Issey Miyake Pour Homme (Silver Mountain Water), and more. Oppenheim describes Olivier as a parasitic playboy with an ungodly amount of charm and charisma, the likes of which could seduce even the most stalwart perfumer, a man who simply walks into a lab uninvited and begins smelling mods without permission. He was drawn to Bourdon when Christian Dior held his Kouros release party next door to his shop, and attached himself to the unfortunate Frenchman from that moment onward. The con-man had his mark.

This is what we're meant to believe. Oppenheim injects this air into his writing, a beleaguered sense of extreme cynicism that permeates every sentence about Olivier Creed. As I read through the timeline of Creed's heist, I found myself thinking that none of it was news, except for Fleurs de Bulgarie. It was never a question that Green Irish Tweed, Imperial Millesime (later changed to Millesime Imperial), Silver Mountain Water, and Original Santal were all Bourdon's creations. Of course they were; the man created Cool Water and Joop! Homme, for Christ's sakes! Bourdon's name was already attached to the rest. I kept waiting to read some deep insight, some probing backstory to the machinations of each perfume, and there was none. The entire gist was simply that Pierre was underpaid for his labor, and Olivier Creed had shrewdly made out. Again, not news.

I didn't need Gabe Oppenheim to rehash old news, information that Luca Turin had revealed years earlier in various online writings and comments. Plus, there are major gaps in his timeline, just as there were for Turin. Nobody has ever touched on the briefs for Bois du Portugal, Neroli Sauvage, Green Valley, or Tabarome Millesime, which seems convenient. Despite all talk to the contrary, there are still some compositions that the fragrance community attributes to Olivier, usually the less successful ones, and Tabarome Millesime has always been one of them. (It makes me want that Millesime more.)

What I did need was an explanation for how Olivier managed to assemble his original "grey cap" line of eau de toilettes. This is where the real money is for any book that purports to analyze Olivier's rectitude. Where did Royal English Leather come from? Vetiver 1948? Royal Scottish Lavender? Epicea? These fragrances all predate the "Bourdon Breakthrough" of 1985's Green Irish Tweed, and were all far more traditional in style. Oppenheim delves into Olivier's "origin story," and his mysterious appearance as a twenty year-old on the doorstep of Soleil d'Or, a little commercial shop in Lille, in 1963. Employees there recount how the young man was his own brand ambassador, with a fully-formed range of products that he claimed were "my creations," implying that he was the perfumer. Oppenheim wonders how this was possible, given that Creed has since explained that the compositions were his father's, and were formulated in the fifties.

At this point, which is fairly early in the book, my eyebrows were raised. I was reading Oppenheim's narrative, and said to myself, "Okay, not exactly convincing me that Olivier is the liar you've made him out to be." The author states, with an air of incredulity:

"The Soleil d'Or further makes the case quite accidentally for Creed's backdating, for a distortion of time no less imaginative than H.G. Wells's. Again, page 41, on these first three Olivier-presented scents:

'They anticipate everything that will characterize his future creations: originality, classicism, simplicity, a mark of real good taste.'

If true, and the fragrances bear Olivier's own imprint, their formulation can't possibly have predated his adulthood or birth." (chapter 3, page 39, Kindle edition)

Why not? There is no answer. The only masculine grey cap Oppenheim explains is Acier Aluminium, but Creed has always said that Acier Aluminium was released in 1973, so who cares? We get a variation of the perfume heist story, this time with Bernard Ellena, Jean-Claude Ellena's brother, again claiming Olivier would appear in his lab uninvited and smell everything. But Ellena makes it sound like Olivier was allowed to do this, and that it was less an invasion of privacy and more a mutually agreed-upon arrangement.

The weirdest part of the book is the chapter about Aventus, which is yet another heist narrative, with Jean-Christophe Herault the mark. Here the logic is warped; Herault is Bourdon's protégé, who knew the older perfumer at a stage of his career when he was fixated on pineapple notes. Once again, Olivier waltzes in, and at this point I wondered why Bourdon hadn't warned Herault of the predatory rich man's scheme. If Olivier was such an ungrateful leech, why wouldn't Herault just tell him, "thanks, but no thanks," and move on? But no, the cycle repeats itself, different only in that this time Olivier allows the young perfumer to publicly take credit for his work. Aventus was such a success, and Olivier had his eye on the exit ramp, so he figured, what the heck? Let the artist get his due. Seems pretty fair to me, and it helped launch Herault's career.

To sum up, the book is entertaining, but it suffers from countless plot holes. The exact origin of the grey caps is never explained. Fleurissimo and the rest of the feminine Creeds, with the exception of Bourdon's Spring Flower and Fleurs de Bulgarie, are excluded from the narrative entirely. (I consider Fleurissimo and the feminines that predate the nineties, like Irisia, Tubereuse Indiana, Vanisia, and Fantasia de Fleurs, to be grey caps also.) Oppenheim's main contentions about Creed's veracity are occasionally warranted, but often exist in an evidence-free vacuum of self-serving speculation. His account of Pierre Bourdon is stilted, cluttered with unnecessary subjective interpretations and interjections, and surprisingly dull. One never gets a sense that the author got to know the master perfumer, and without that, what else can a book like this offer? I might have enjoyed the read more if I'd felt the story was organic, self-forming, its author learning along with me, but instead it was merely a belief in search of validation.