|

| "Donald, this smells familiar." |

This weekend I was on Reddit. I know, I know. What was I thinking? There was a thread on Creed titled "Creed company's origin? How are they getting away with a fake story" -- and I had to pitch in my two cents. I know, I know, I know. What was I thinking? It's not bad enough that Reddit is populated with ignorant trolls that ceaselessly babble about stuff they know nothing about; they occasionally venture into interesting territory, and turf up just enough nonsense to lure the likes of me right on in. And boy, was I in.

The gist of the thread was that Olivier and Erwin Creed are liars who have conned the world, ala Gabe Oppenheim's The Ghost Perfumer. Nothing new there, folks. I've already hashed and rehashed my opinion on that. But just to choke it up again, and I'll be as succinct as possible here, it's not all that bizarre for Creed to do that. Did they stretch the truth on multiple occasions? Did they exaggerate their pedigree to make their brand more appealing? Did they "con" the world with dubious claims about royal appointments and a three hundred year legacy? Maybe. Sure, maybe they did.

But let's be honest here, people. We know what the Creeds were doing. It all made sense. They have an old family that does date back several generations, and their forefathers were in the fashion biz. They were in the "riding habits" biz. Eighteenth century leather makers like the Creeds were in a sophisticated business, one which entailed the production of leather goods, but which also required such goods to be palatable to the public, and in the 1700s, that meant making the leather smell like something other than disgusting raw animal hide. Gee, I wonder what would make dead skin smell good?

Aside from that, James Henry Creed and all the Creed tailors of that bygone era were busy making saddles and boots and gloves and jackets, and probably also made saddle soap, powders to condition and scent the gloves, little olfactory trinkets to scent the boots and jackets and get rid of the nasty. Every high-end leather maker since the dawn of time has done that. Every tailor dealing in "sports" equipment dating back to Caesar has done it. Can we stop pretending we don't know this?

This gets me back to the Reddit thread. On this thread were numerous young men who were all about pretending they don't know everything I've just said. It was all about how the Creeds are liars, con men, they have "no evidence" of perfuming anything prior to 1970, how do they get away with the lies, the lying liars that lie?

One guy commented:

"If you want a company with REAL history just go with Guerlain."

Another guy said,

"They claim to have made fragrances for the likes of Winston Churchill and such, but there is no proof. Compare that to Guerlain who has an extremely well documented history. Creed = lies lol."

And yet another said:

"My take is Creed is probably 50 or so years old and the rest is marketing to convince you that bottle of perfume that cost $10 to produce is worth $500."

This was followed by a response from another user:

"Not true. There are actual receipts etc from the 1800s for tailored goods and royal warrants. The original store in Paris has the actual warrant from Napoleon framed in the store. There is history to the Creed brand but not just for making perfumes. Doesn't matter if they embellish things a little, every company does for marketing reasons."

This prompted a response from the other guy:

"Can you provide a link to a verifiable document? Up until as recently as 2 years ago no documents could be verified anywhere. There seems to be a long history of no documentation, including a total absence of warrants. If they have proof in their shop it seems reasonable the rumor would have ended."

This led to me saying:

"My friend, you clearly don't know what you're talking about. You want to see Creed's royal warrant? Just look at any one of their Private Collection boxes. Their warrant with royal signature is printed on the back of every one of them. I get it's fun to criticize Creed. But you've just embarrassed yourself.

This got a windy response that ended with the sentence:

"If you have something objective to add, let's see it."

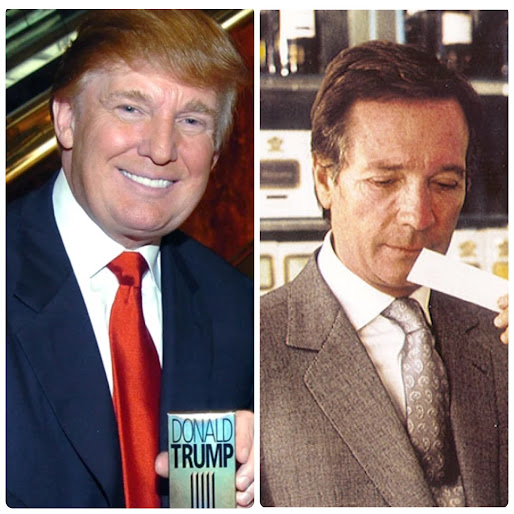

I posted this photo:

It has the royal warrant clearly displayed. The guy had claimed that he owns Private Collection fragrances and that none of his boxes have the warrant on them, but when I posted this picture he shut up right quick and I haven't heard from him again. Conversation over, as it should be. (Pretty clear the only lie on the line was the one about owning Private Collection Creeds, as evidenced by how easy it was to shut this guy down.)

This got me thinking about how people grapple with what I call the Creed Conundrum. I’ve written about this before: there’s something about Creed that seems to cloud rational thought. Call it Creed Derangement Syndrome: an obsessive need to heckle the brand, accusing it of fabricating its entire history. The prevailing narrative? Olivier Creed conjured the whole legacy out of thin air, hired modern perfumers to craft the scents, and let the truth be collateral damage. And if I don’t buy into that outrage, well, then clearly I must be a gullible fool, a perfect mark for this suave charlatan and his so-called phony empire. How could I be so naive? What’s wrong with me?

This is the same dynamic I see with Donald Trump. For example, he steps up to a microphone in front of a crowd and says something like, "I love Mexicans and Mexico, they’re wonderful people. But they’re not sending us their best. The people crossing the border are drug dealers and rapists." Okay, it’s a bit uncomfortable, I’ll admit. The phrase "I love Mexicans" is meant to soften the impact, but I have to carefully unpack what Trump is actually saying: he believes that many illegal border crossers are young men with bad intentions, no viable way to earn a living in the U.S., and likely to engage in more criminal behavior while here. Laken Riley’s family would probably agree with him on the issues of drug dealers, killers, and rapists.

I then sit back in my chair, and think, "Well, he didn't say that very well. And he's not as clear as he could be. He's trying to say that Mexico and Mexicans are generally likable -- lovable, even. He likes them. But the border problem is the worst of Mexico mixed in with some of the others, and it's those baddies that we need to focus on, because if we're just letting them into the country, no questions asked, we've got trouble."

Then I turn on the news.

The chyron: . . . TRUMP SAYS MEXICANS ARE DRUG DEALERS AND RAPISTS . . .

And I sigh. That's not what Trump said. It's on tape. I know what he said. Why are you gaslighting me on what he said? It's the border. We've been having issues down there for decades. They've been getting much worse in the last twenty years. He's addressing that. He's making his case. I don't particularly like how clumsily he's making it, but he's making it, and I get it. Why are you pretending you don't get it, mainstream news people?

Trump addresses the Charlottesville fiasco with the Confederate statues, and says that in the debate about whether the historical aspect of those statues should be preserved, there are "Very fine people on both sides." The mainstream media and the Democrat party interpret that as, "Donald Trump says white supremacists are very fine people."

Again, not what he said.

In 2024, much of these gaslighting messaging tactics have been debunked on X, Elon Musk's platform after his Twitter buyout, and the majority of Americans now have a revised opinion on exactly what Donald Trump stands for, which explains how a majority of voters put him back in office, including about 50% of hispanic voters (mostly men). Now, whether or not that was a good thing is up for very deep debate, and there is a strong case to be made that Trump should not serve another term, and should perhaps serve jail time instead. That case is convoluted, hard to understand, impossible to identify with. I don't get it. Neither do 75 million Americans. But, there is another 75 million who do get it, and to them it's very real. I can live with that. I can work with that. I can respect it.

I bring this up because the same thing happens with Olivier Creed. Olivier does an interview and says to Le Figaro in 2013, "When I entered with my creations exclusively in a provincial perfume store like Le Soleil d'Or, in Lille, in 1963, it was a real challenge against the big brands." Gabe Oppenheim translates this to: "Perfumery was a brand new business for us, so I chose to soft-launch it in the sticks."

That's not what Olivier said.

He clearly said that he positioned himself in a provincial commercial setting because he was up against the likes of Chanel and Dior. He's stating that when you take your perfumes from the land of bespoke and into the designer market, you have an uphill battle on your hands. What Olivier is implicitly saying is that when your perfumes have to speak for themselves because you don't have a rich financial backer to foot the bill, and your own money is at stake, wealthy as you may already be, it's still a major uphill battle. For comparison, look at how Pierre Montale made out. He was also a "perfumer to the royals" in the Middle East. Despite that, he still needed a rich financier to fund his launch of the Montale brand. Without that, and despite all of his private clientele, he wouldn't have gotten his own perfume business off the ground.

Olivier has honesty on his side there, the same sort of honesty that Donald Trump kinda-sorta has when he kinda-sorta just is himself and says exactly what he thinks, at least in the moment he thinks it. But here's the thing about Olivier Creed, the thing that Trump doesn't have: he's got mystery on his side. Yes, there are things about Olivier and the Creed dynasty that are not known to the public. He has kept it that way for a reason. Mystery about him and his family gives him cover.

This cover creates a vacuum of information and knowledge, which gets filled with speculation. But like with Trump, the speculation is touted as fact. "Creed's perfume business only dates back to the seventies." "Creed lies about the perfume part, but the tailoring business was real." "There is no verifiable proof that Creed created perfumes prior to 1970." All of these ideas swirl around in the bleakness that Creed's mystery has cast on the yearning public, those fragrance-obsessed guys who spend all of their time seeking out and buying the most obscure niche crap they can find.

The claim that Olivier started the perfumery end of the Creed family business is tempting to believe. There are a slew of factual arrows that point in that direction, and many are mentioned in Oppenheim's book. Indeed, Creed did show up at Le Soleil d'Or in nineteen sixty-something with a couple of perfumes that had no clear provenance, and he was, by his own account, looking to sell. He claimed to be a perfumer. He continued to offer perfumes to the shop, and as Oppenheim's book elucidates, those perfumes actually moved units. Oppenheim acted like the number of perfumes that sold was meager, but I was impressed by it. Twelve-hundred bottles sold in 1970? That's a hundred sold every month. That's about three bottles per day. For a small family brand with no designer clout, that's amazing.

My problem with all of this is that it doesn't track. Just as the slings and arrows fired at Donald Trump fail to land, the same degree of skepticism thrown at Olivier Creed misses the mark and hits something else entirely. Oppenheim fails to deliver the goods on my questions about where Olivier got the "Creed Water" formula of real ambergris and musk from, or how he came up with his impressive list of briefs for the Grey Cap lineup. You can say a guy pulled briefs out of his butt, conned a few perfumers into making them, and touted them as heirlooms . . . but he pulled this off with Fleurissimo, Orange Spice, Épicea, Baie de Genièvre, Bois de Cèdrat, Citrus Bigarade, Sélection Verte, Bayrhum Vétiver, Herbe Marine, Ambre Cannelle, Angélique Encens, Aubépine Acacia, Bois de Santal, Santal Impérial, Chèvrefeuille, Animalis Pimenta, Bois de Rhodes, Cyprès-Musc, Ylang Jonquilles, Royal Scottish Lavender, Cuir Imperial, Verveine Narcisse, Vétiver, Fleur de Thé Rose Bulgare, Irisia, "Vintage" Tabaróme, Royal English Leather, and Zeste Mandarine Pamplemousse?

Sorry, Gabe, but no.

There is a huge chunk of information missing here. Most of these perfumes aren't color-by-numbers pieces; they are weirdly sophisticated and speak to the sort of Old Money wealth that only aristocratic Europeans enjoy. You can't fake that. You, Mister Oppenheim, have failed to shed light on most of this.

The skeptics sling everything they can at this, and miss every time. The word they like to use that gives away their bad aim?

"Proof."

They want "proof" that Creed is responsible for creating perfumes prior to 1963. What they ought to be asking for is "proof" of who is responsible for the lion's share of perfumes that predate Green Irish Tweed, and fundamentally question whether the perfumers who have laid claim to some of them, like Pierre Bourdon did with Fleurs de Bulgarie, were acting on brand-new from-thin-air briefs, or adapting archaic, time-worn formulas that needed overhauls to be brought to commercial market. Almost nobody is asking about that.

The narrative that Olivier Creed simply waltzed into labs and stole formulas is more entertaining, even though it doesn't really make sense when you consider the scope of the lineup mentioned above.

If I had a leather riding goods and tailoring firm in the 1700s, my focus would be on the functional accoutrements to leather. This was a time when perfume barely existed. I would create products like saddle soap and homespun perfumes designed to make the hide smell tolerable. The formulas I developed would be proprietary to my leather goods firm. If they proved successful in their duties over the course of a century, I might parlay one or two of them into actual fine fragrance at some point in the nineteenth century.

These perfumes would be little stocking stuffers offered to faithful clients in tiny bottles of an ounce or less. They might even gain some steam in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when the leather goods end of things has closed shop, and the tailoring has picked up. By the middle of the twentieth century, I might have some period-specific pieces on offer like Orange Spice and Fleurissimo. These might migrate from the 1950s to the 1960s, into the hands of a young Olivier Creed, who might eventually decide to "amp up" the perfume piece and make it everything.

None of this is hard to believe. None of it requires proof.

Orange Spice, by the way, is an example of a perfume that I think adds to the Creed mystery. Pierre Bourdon is not the nose behind it, despite its resemblance to Kouros. If he were, the formula would have been mentioned in Oppenheim's book, and it wasn't. (Varanis Ridari has the scoop there.) I smelled the comparison to Kouros in my bottle, but I also smelled a strong comparison to another fragrance from the 1950s called Max Factor Signature for Men. Same musky orange and wood notes. Slight hint of ambergris and nitromusk in the base. The two fragrances clearly hail, at least in spirit, from the same era. That goes a ways in backing up Creed's claim that Orange Spice is from 1950.

That might sound trite, but the truth is less glamorous than the narrative we've been spoonfed by the skeptics. Again, anything is possible, but if Creed faked the provenance of Orange Spice, well then, man, did he nail it. Total bullseye. He managed to get a perfumer to make up something that smells quite literally like some obscure fragrance from the 1950s, which happens to also be in my collection.

The Reddit user is right to say that Guerlain has real history to prove they made perfumes. Creed isn't Guerlain. Guerlain is a behemoth of nineteenth and early twentieth century perfume; Creed is a footnote. When Pierre-François Pascal Guerlain was gunning for a spot in the Eau de Cologne Hall of Fame, Creed was merely doing private little ditties for wealthy clientele. Privately-commissioned fragrance. This is what Olivier Creed and his son, Erwin, have claimed their family dealt in for hundreds of years.

There would be zero proof of any privately-commissioned perfumes. They would not come in mass-produced bottles. They would probably be delivered in little apothecary bottles. And they would not have advertising or a paper trail of any kind, beyond whatever perishable receipts of the tax year might require.

None of this is hard to believe. None of it requires proof.

These formulas, probably a bit hackneyed and unscientific, unsophisticated even, would eventually need to be made in earnest by trained perfumers, if they were to survive at all. Cue the 1970s. Cue Olivier's quest to hire professionals on the low-down and make things properly. Suddenly Fleurissimo exists in a mass-produced flacon with a label and anyone with money can buy it.

None of this is hard to believe. And the proof is in the perfumes.

Why must we go all Trump Derangement Syndrome on Creed every single time the subject of their historical bonafides comes up? Must we keep pretending that Creed's claims about making perfume are preposterous? The part about making the perfumes, I mean. If you want to poke holes in all the claims about serving perfume to royals, have at it. But making the perfumes. Really? We can't believe that some Creed sometime before 1963 came up with a few perfumes? Even if they were purely functional perfumes used to soak leather hides and give them a signature smell? Scented gloves for ladies? Scented habits for riding? The stuff that people actually used back then, as opposed to the luxury stuff of today that people don't need to use?

Is it the fake tan thing? If Olivier's tan was real, and not orange, would he be more credible? Or still in the doghouse like Trump? Has Olivier, in being a successful businessman with a knack for exaggerating his accomplishments, harnessed the unfortunate power of "Orange Man Bad?"

The moral of this article is the following: Stop expecting proof of things that never required proof prior to you coming along and demanding it. If a family made bespoke perfumes for wealthy Europeans dating back hundreds of years, those Europeans would have had titles and nobility. That's how Europeans with money rolled back then. If you had money, it was likely inherited. And it was disposable, and even then, it was used for frivolities like fancy riding habits with citrus and floral scents. Such personal bespoke projects would not survive in any way to yield "proof" of their existence centuries later. They would simply melt into the annals of time. If this is what the Creed family did, then the only proof they need is the warrant printed on the box. Read it, and shut up already.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)