12/24/24

Hawas (Rasasi)

12/22/24

Dark Cherry & Amber (Banana Republic): A Claude Dir Mod for Creed's Carmina?

When I was in high school, one of my so-called friends regularly invited me and a few others for rides in his 1980 Cadillac de Ville. He wasn't so much a friend as he was an experience: he wore the original Aramis, chain-smoked Marlboro Reds, chewed Wrigley’s Winterfresh gum, and when he wasn’t drinking cheap beer, he clung to Cherry Coke like it was an endangered elixir. Occasionally, he’d offer me a can. I almost always declined. Cherry Coke, for all its cultish charm, never resonated with me—its cherry flavor felt like a rumor, faint and unconvincing. It wasn’t just the soda. Cherries, whether eaten, scented, or artificially flavored, have always felt elusive to me, like an ephemeral note in a song I couldn’t quite catch. Even into adulthood, cherries remain little more than a passing suggestion, an essence that flits and fades before it takes root. This curious shortfall in my sensory lexicon is particularly relevant when it comes to Dark Cherry & Amber.

Cherry, as a perfumery note, has long been one I approach with caution. Tom Ford’s indulgent maraschino cherry fragrance, which I reviewed in January, was an exception, registering with clarity and punch. Joop! Homme, for all its brash artificiality, blares its cherry note with unapologetic gusto. Beyond those two, my encounters with cherry scents have been sparse. Enter Dark Cherry & Amber, a fragrance whispered about in perfumery circles as a hidden gem, praised for its quality at a modest price. For years, I’d spotted it at Burlington Coat Factory, an unassuming presence on the discount shelves. But then came Creed’s Carmina in 2023, and Dark Cherry & Amber seemed to vanish overnight, its elusive reputation only growing. The buzz around Carmina suggested it was an upscale reimagining of Claude Dir’s 2019 composition for Banana Republic. That theory gained traction when Derek (aka Varanis Ridari) likened the two with the assertiveness of a Brooklyn chess hustler. After I read his theory, finding a bottle of Dark Cherry & Amber became an obsession. Fifteen months later, my search finally bore fruit today, at a Burlington in Orange, Connecticut.

Of course, I have a problem: I’ve never smelled Carmina, so I can’t confirm the comparison. Still, there are clues. A user on Fragrantica, “ayshee_x,” described Carmina shortly after its release:

“Smells kind of nostalgic, like cherry lip gloss and plastic but also floral and musky. There are better cherry perfumes out there that are cheaper. Banana Republic Dark Cherry & Amber is a great alternative and a fraction of the cost.”

At twenty dollars, Dark Cherry & Amber certainly wins on price. But what about the scent? It opens with a juicy, lifelike cherry note that eschews the romanticized maraschino of Tom Ford for something startlingly natural. It’s as if someone bit into a ripe Bing cherry and waved it under my nose—your everyday table cherry, unvarnished and unadorned. While this might sound uninspired, Dir leans into its simplicity, rendering it strikingly authentic for the first hour. There’s a dusky, sweet-tart fruitiness to the note, accompanied by a faintly soapy “off” quality that mirrors the idiosyncrasies of an actual cherry. It’s an impressive feat for a fragrance at this price point, the Tea Rose of cherry perfumes.

After that start, the cherry begins to retreat, making way for a smooth, luminous vanilla amber. On paper, the amber reads as floral—cherry blossom, perhaps—while on skin it veers toward a warmth reminiscent of praline, though it never fully commits to gourmand territory. Beneath this lies a subtle woodiness, like a watercolor wash of sweet blossoms and watery cedar. The effect is delicate, almost ethereal, and I can’t help but wonder how many high-end niche houses passed on this gem before Banana Republic picked it up. At its core, Dark Cherry & Amber doesn’t pretend to be lavish. It doesn’t aim for the baroque richness of ultra-luxury niche brands. Instead, it offers something far more elusive: clarity. A lucidity that reminds me of my old Cherry Coke dilemma. Just as I struggled to taste the fruit in the soda, I find the cherry here to be restrained, a gentle presence rather than a cloying shout. I sense its tartness, its juiciness, but it often lingers at the edge of perception, never overwhelming.

And that’s precisely why it works. Had the cherry screamed for attention, it might have felt cheap, like a budget air freshener cherry. Instead, it whispers, and in that quiet confidence lies its charm.

12/15/24

Luna Rossa Ocean Le Parfum (Prada)

The Luna Rossa Ocean line is intriguing, particularly because the concepts behind these fragrances are often misunderstood—sometimes wildly so. To put it simply, people expect these to be bog-standard aquatics because "Ocean" is in their name. There's also a forest-for-the-trees element, where folks mistakenly think that the artistry of perfume rests solely in note pyramids, while altogether missing that disparate notes like saffron and oak can be tied together to create a pastiche of something cool and salty, like the sea. While I won’t delve into those broader misconceptions here, Ocean Le Parfum serves as a prime example of how a fragrance can reveal people's “olfactory conditioning.” This so-called “Red Moon” fragrance is an aquatic—a profoundly good one—but much of the general public overlooks this because it doesn’t conform to aquatic tropes.

Many perceive it as a spicy-woody amber scent, full of cinnamon, saffron, and modern oriental flourishes. And yes, those elements are present, especially saffron, which is prominent. But the real magic is not in each note, but in how they all coalesce: they merge into a sparkly synthetic ambergris. The mystery perfumer combined materials like Amber XTreme (IFF) and Safranal (Givaudan), forming a silvery mineralic amber accord that creates its own little glittering in the nose, so to speak. The result captures the essence of summer beach air, cushioned with a warm freshness that’s far removed from the lavender and fruity notes typical of designer aquatics. This isn’t the romanticized scent of seawater or “blue” accords dominated by Calone and Melonal. Instead, it’s the sensory experience of being in and around the ocean. There's hot pepper for animalism, and a woody-amber sand. The concept is “Ocean,” but the execution captures how your body feels and responds to it, rather than directly mimicking marine notes, and that is what you pay for here. This fragrance is from the Ocean Rain school of aquatics, not Acqua di Giò.

It's also an exceptionally thoughtful birthday gift from two members of my family, and I cherish it even more because of that. With designer lines now priced alongside niche competitors, acquiring 100 ml of Luna Rossa Ocean Le Parfum would’ve been out of reach without their generosity. For me, this fragrance still leans “aquatic” in spirit, despite what others may say. And to those who insist it’s merely a spicy oriental, the YouTubers who write it off as not meeting their expectations because it isn't a member of the blue-bottle brigade, I say, just enjoy it. This is a truly unique creation. If you’ve never traveled or experienced the ocean, this scent will transport you there. Don’t let the red packaging mislead you—this is a 21st century ambergris dream.

12/13/24

Face à Face pour Femme (Façonnable)

Designer brand Façonnable launched Face à Face pour Femme and Face à Face pour Homme in 1996. While never particularly expensive, they were a step above bargain-bin pricing at the time. Slightly pricier than offerings from Jacomo or Beene, some of the cost likely went toward packaging—Façonnable favored embossed tins over standard cardboard boxes. Setting aside the presentation, the fragrances themselves are solidly middle-tier: competent and occasionally engaging but neither groundbreaking nor especially memorable, with materials falling a notch or two below those of Chanel or Dior. Face à Face pour Femme bears a surprising resemblance to Grey Flannel, reimagined with subtle adjustments for a more feminine appeal. Unlike the Beene classic, it omits citrus entirely, opening instead with coriander, which lingers through the top and early heart notes. This gives way to a crisp yet dry-green medley of rose, muguet, and jasmine. The green notes are stemmy, grassy, bitter, and powdery, while the floral tones remain dry, faintly sweet, slightly bitter, and heavily powdery. There’s little warmth or cheer here—this is a fragrance with a reserved, almost austere demeanor.

The sweeter, slightly brighter floral tones in Face à Face pour Femme evoke comparisons to both Grey Flannel and Silences. This is undeniably a "fresh" fragrance, but it’s a 1990s kind of fresh, so if you’re under 35, consider this fair warning. Don’t expect airy peonies, aquatic accents, or the sugary burst of green apple and white musk typical of more modern compositions. Instead, Face à Face pour Femme tempers its floral character with a smooth greenness reminiscent of tea, much like vintage Grey Flannel. Around the three-hour mark, its vaguely floral, slightly dry, and chalky personality—likely due to inexpensive galbanum notes—settles into a powdery green accord. Here, grasses, oakmoss, and a recurring green tea nuance intertwine subtly. I enjoy this fragrance, but its particular style feels like a hall of mirrors, inviting nostalgia lovers to lose themselves in endless panels of Moss-in-Snow jade. It’s a 29-year-old scent that feels like fragrances twice its age. Still, it's a charming throwback, and good fun.

12/9/24

Chameleon (Zoologist)

12/8/24

Maritime Journey (Tommy Bahama)

The original Maritime from 2016 is Tommy Bahama’s answer to Abercrombie’s Fierce, while Journey (2019) serves as their take on Polo Ultra Blue. In fact, I suspect it may be an unused mod for the Ralph Lauren scent that Tommy Bahama repurposed to meet their brief. Had it been crafted on a Ralph Lauren budget, it might have achieved a closer likeness, but Tommy Bahama has always occupied the lower shelf in the fragrance aisle. As a result, Maritime Journey comes across as a bit rough around the edges, scratchier and cheaper (it makes me sneeze), yet serviceable at just ten dollars an ounce.

Unlike Ultra Blue, Maritime Journey features a prominent green apple note and lacks the herbal undertone. Otherwise, it’s a fruitier spin on the familiar sea salt and woods accord that has dominated aquatics since the early 1990s. Here, the Calone molecule is restrained, adding a faint blush of peachy warmth to a grey-blue profile. While it teeters close to the realm of shower gel freshness, it maintains just enough balance between sweetness and saltiness to feel adequately refined. It’s light, non-offensive, and versatile, a competent choice for men seeking value in their cologne. However, with so many similar options already on the market, Ultra Blue remains the superior pick for but a few more dollars. Maritime Journey’s only standout feature is its pronounced saltiness, which borders on excessive, even for an aquatic enthusiast like me, but otherwise, it’s not worth going out of your way for a bottle.

Interestingly, this stuff also evokes shades of the original Cool Water (1988). Its sharp Granny Smith apple note has the same tart, low-pH quality, and when paired with sea spray and faint floral-cedar nuances, it carries a hint of that late-80s vibe. The synthetic saltiness nudges it into the 21st century, but you’d be better off spending your $23 on Cool Water. For a softer, less saline alternative, Nautica Voyage would suffice. Fragrances like this are akin to grey-blue paint chips on a Benjamin Moore sample page: pleasant enough, but somewhat boring and ultimately forgettable.

12/7/24

Rhinoceros (Zoologist)

Gentleman’s Club fragrances ruled the 1980s, but Cool Water toppled their dominance, and Acqua di Gio sealed their fate. By the late 1990s, few dared to replicate the style, leaving woody tobaccos and patchoulis to linger as relics of a bygone era. As the new millennium began, these notes found refuge in the niche perfumery world, and eventually led to Prin Lomros’s 2020 reissue of Rhinoceros.

The more I wear Zoologist fragrances, the more their mission crystallizes: resurrect the classic, complex masculines of the past and transform them into animal-themed haute parfumerie at $100 an ounce. If you’re a devotee of vintage greats like the original Davidoff (1984), Bogart’s Furyo (1988), or Vermeil for Men (1995), Rhinoceros will feel like liquid Xanadu. Lomros has packed the composition with leather, incense, chocolatey patchouli, cypriol, oakmoss, and oud, with each note discernible yet blended into a saturnine olfactory sienna. To Western noses, it reads unmistakably “masculine.”

I used to wear fragrances like this daily, and truthfully, they are wonderful. It’s hard to fault the seamless accords of whiskey, rum, Connecticut shade, and oak. Even the slightly skanky oud is palatable. Yet, as much as I admire its artistry, Rhinoceros feels like a time capsule. Imagining it worn in 2025, when the world and its men have moved on, is a stretch. I applaud Zoologist for boldly releasing something so unapologetically “1987,” but I caution any young buck against believing this will captivate today’s woman. Times have changed, even as the memory of this style endures.

11/25/24

Gold (Commodity)

Donna Ramanauskas, the creative force behind Gold and several other Commodity fragrances, has a style that's unmistakably her own. It’s light and energetic, fresh yet palpable, with an edge that flirts with challenging notes like inedible vanilla and sharp cypress. These two elements dominate Gold, resulting in a fragrance that, while not particularly daring, carries an air of sophistication. The interplay of crisp woods and soapy vanilla feels polished, even if it doesn’t venture far from the designer amber path.

Oriental and amber fragrances rarely hold my attention. They often grow monotonous and lean into a cloying femininity that I tire of quickly. Gold, however, sidesteps these pitfalls by weaving in nuanced layers. Its vanillic amber is softened with a touch of benzoin and an almost otherworldly synthetic sandalwood. This sandalwood doesn’t aim for authenticity but instead provides just enough weight to prevent the composition from floating into oblivion. Iso E Super hums in the background, its woody vibration threading through the drydown, where transparent wisps of vanilla and white musk add a cool, breezy texture. If you’re torn between smelling clean or cozy, Gold offers a compromise, though one that leaves me wishing for a fragrance that's a bit more natural-smelling and daring.

Vanilla reigns supreme in Gold, but this is a hyper-modern interpretation, stripped of imperfections. It’s a flawlessly smooth, almost digital note, devoid of spice, warmth, or romance. Some might find solace in its unerring refinement, but I long for a richer balance, something earthy, like the clove-heavy nostalgia of Old Spice, something alive. Gold is a masterclass in technical precision but lacks the soul to make it truly memorable. I expect a perfume to move me on an emotional and intellectual level, especially if it's named after what I must fork over to own a bottle. Gold leaves me cold.

11/24/24

Sandflowers (Montale)

Here’s the thing about Sandflowers: I wanted a "true" aquatic, something that evokes the cold, briny wave of the ocean crashing on icy boulders and the gritty, coarse texture of New England sand, ground fine by centuries of waves and worn shells. Frigid, salty, with spray drifting in the air, it should carry heady notes of iodine and seaweed, but nothing of the typical funk of low tide, except perhaps the most delicate hint. And that is exactly how Sandflowers smells. No sweetness. No flowers. Salt water. Period. End of story.

What accounts for this fragrance's precision? How did Pierre Montale, known for his dense rose/oud blends and heavy, sweet musks, manage to craft something so seemingly out of character? By what act of grace did an anonymous perfumer in a Parisian lab offer up this peculiar tribute to a Connecticut beach in December? For me, it’s a hauntingly beautiful composition, the ideal aquatic for trips to Maine, where even miles inland, the air carries the cool, clean scent of the Atlantic, filtered through pine needles and campfire smoke. Sandflowers is as ethereal as that, a light, salty draft on crisp, winter air. And contrary to the consensus of many reviewers, I don’t detect anything sandy in it. For sand, one would be better off with Mario Valentino’s Ocean Rain.

Sandflowers smells salty, like skin after a day on the open ocean. But it needn’t be the frigid Atlantic of Maine. In 2004, I rented a speedboat with friends to explore the grottos of Capri, where we glided over gentle green waves in ninety-five-degree heat. The water was oddly salty, even by oceanic standards, its spray drying on my skin in a layer of salt that flaked off in the sun. By the end of that day, I smelled exactly like Sandflowers. Montale has put great care into this fragrance; aside from a fleeting, almost antiseptic alcoholic top note (mated to cinnamyl alcohol) that evokes the smell of a razor sterilizer, the composition is a resounding success, and a dream for aquatic lovers. Excellent work.

11/18/24

The Trump Anomaly: How Olivier Creed Accidentally Harnessed the Unfortunate Power of "Orange Man Bad"

"If you want a company with REAL history just go with Guerlain."

Another guy said,

"They claim to have made fragrances for the likes of Winston Churchill and such, but there is no proof. Compare that to Guerlain who has an extremely well documented history. Creed = lies lol."

And yet another said:

"My take is Creed is probably 50 or so years old and the rest is marketing to convince you that bottle of perfume that cost $10 to produce is worth $500."

This was followed by a response from another user:

"Not true. There are actual receipts etc from the 1800s for tailored goods and royal warrants. The original store in Paris has the actual warrant from Napoleon framed in the store. There is history to the Creed brand but not just for making perfumes. Doesn't matter if they embellish things a little, every company does for marketing reasons."

This prompted a response from the other guy:

"Can you provide a link to a verifiable document? Up until as recently as 2 years ago no documents could be verified anywhere. There seems to be a long history of no documentation, including a total absence of warrants. If they have proof in their shop it seems reasonable the rumor would have ended."

This led to me saying:

"My friend, you clearly don't know what you're talking about. You want to see Creed's royal warrant? Just look at any one of their Private Collection boxes. Their warrant with royal signature is printed on the back of every one of them. I get it's fun to criticize Creed. But you've just embarrassed yourself.

This got a windy response that ended with the sentence:

"If you have something objective to add, let's see it."

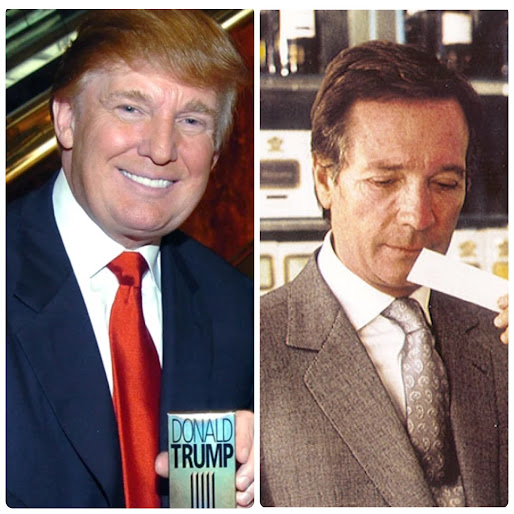

I posted this photo:

It has the royal warrant clearly displayed. The guy had claimed that he owns Private Collection fragrances and that none of his boxes have the warrant on them, but when I posted this picture he shut up right quick and I haven't heard from him again. Conversation over, as it should be. (Pretty clear the only lie on the line was the one about owning Private Collection Creeds, as evidenced by how easy it was to shut this guy down.)

This got me thinking about how people grapple with what I call the Creed Conundrum. I’ve written about this before: there’s something about Creed that seems to cloud rational thought. Call it Creed Derangement Syndrome: an obsessive need to heckle the brand, accusing it of fabricating its entire history. The prevailing narrative? Olivier Creed conjured the whole legacy out of thin air, hired modern perfumers to craft the scents, and let the truth be collateral damage. And if I don’t buy into that outrage, well, then clearly I must be a gullible fool, a perfect mark for this suave charlatan and his so-called phony empire. How could I be so naive? What’s wrong with me?

This is the same dynamic I see with Donald Trump. For example, he steps up to a microphone in front of a crowd and says something like, "I love Mexicans and Mexico, they’re wonderful people. But they’re not sending us their best. The people crossing the border are drug dealers and rapists." Okay, it’s a bit uncomfortable, I’ll admit. The phrase "I love Mexicans" is meant to soften the impact, but I have to carefully unpack what Trump is actually saying: he believes that many illegal border crossers are young men with bad intentions, no viable way to earn a living in the U.S., and likely to engage in more criminal behavior while here. Laken Riley’s family would probably agree with him on the issues of drug dealers, killers, and rapists.

11/11/24

Replica Sailing Day (Maison Margiela)

Briny aquatics thrive when they embrace their salt-soaked nature without being softened by fruit or generic crowd-pleasing notes. Maison Margiela’s Sailing Day, launched in 2017, attempts an intriguing balance but falls oddly short. It’s loaded with the essentials: sea salt, seaweed, minerals, aldehydes, and Amboxide, yet lurking beneath the surface is an unexpected sweetness, a soapiness verging on dish detergent. Ajax in my high-end fragrance? Who authorized this?

The scent opens with a sharp burst of frosty aldehydes, anchored by an intense saline note reminiscent of opening a jar of Himalayan pink salt and inhaling deeply. Yet somehow, this bracing saltiness is layered with a bubble bath-like sweetness, as if Sailing Day were more suited to a toy yacht in a soapy tub. A faint trail of white florals and a timid hint of pineapple-citrus runs through it all, but nothing takes center stage. Ultimately, Sailing Day is a steady, linear composition, smelling good but landing somewhere between commonplace and, well, “meh.”

I view aquatics like this one as the go-to for people who are still unaware of their options. Having sniffed my way through a hundred or more variants in the aquatic genre, I know what truly shines in this category. Yet for many, Sailing Day may simply register as an inoffensive “luxury” spin on a “fresh” and “sexy” locker room scent. And perhaps that’s all Maison Margiela aimed to achieve. For the less discerning, it does the job well enough, and in that spirit, I give it a reluctant nod of approval. (Get Sel Marin instead.)

11/10/24

Obsession for Men -- Oops! I Mean, Musk Deer (Zoologist)

This 2020 creation from Zoologist, crafted by Pascal Gaurin, senior perfumer at IFF, immediately transported me back to the 1990s. Now, for those of you who’ve been following my writing for some time, I’m aware that my frequent nostalgic musings about this era might be a bit much. But I stand by it: the 1980s and 1990s were a golden age of cultural innovation, and I often find myself yearning for the heady days when fashion, music, and fragrance had a particular magic. One standout from that time was Calvin Klein's Obsession for Men, a balsamic oriental fragrance rich with resins and spices that exuded a "grown-up" sophistication without veering into stuffy territory. Though the fragrance has been reworked over the years, its essence remains intact, albeit a few notes lighter than I remember. (For this reason, I haven't purchased a new bottle.)

Obsession wasn’t merely a fragrance; it was an olfactory phenomenon, a marketing blitz that was impossible to ignore. From every magazine cover to every television ad, Kate Moss, scantily clad, if at all, stared provocatively back at me, stirring up all the hormonal chaos of a teenage boy. The scent, an "adult" oriental, was paired with imagery of waifish women caught between raw sensuality and a hint of rebellion. It was an audacious marketing strategy, but undeniably effective, selling a dream of dangerous allure. Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling that Obsession was just a little bit aspirational, like even those who wore it might have done better with something just a touch more refined. But there was no such version until now.

Pascal Gaurin answered the likely implicit call of creative director Victor Wong to reimagine Obsession, and the result is Musk Deer, a fragrance that takes the foundations of Klein’s iconic oriental and elevates them with the finest materials available. Gaurin, having crafted eleven fragrances for Calvin Klein, clearly knows Obsession inside and out. He has, in essence, "Creedified" it, giving us a scent that is both familiar and refreshingly new. Musk Deer is a stunning, crisp oriental that channels the rich amber and animalic-floral notes of the original, while introducing a new complexity through layers of cedar, labdanum, patchouli, and a delicate touch of natural Laos oud. At the heart of this composition is a luminous Sambac jasmine absolute, which infuses the fragrance with a velvety, almost intoxicating sensuality. It's a cheap-in-a-fun-way smell done with an unlimited budget.

Among the entire Zoologist collection, this fragrance feels the most wearable to me. In fact, it’s the one I’m seriously considering purchasing. Obsession has always held a special place in my heart, and I’ve long hoped for something that could take its core concept and refine it. With Musk Deer, I’ve finally found that dream realized. Much like the original Obsession, this fragrance evokes a strangely alluring fantasy: a vision of youthful, ethereal women existing in a quiet, almost surreal world of sterile, colorless advertisements, where the only thing that matters is how good they smell. Spray on Musk Deer, and it’s the 1990s once again. Only this time, I’m ready for the ride.

11/3/24

Replica When the Rain Stops (Maison Margiela)

"When the Rain Stops is supposedly inspired by Dublin in 1967. I wasn't alive yet in 1967, but I do remember, somewhat acutely and unwillingly, what Dublin smelled like in the early 80s. It wasn't like this. There's a distinct lack of diesel fumes, smog, deep fried breakfast foods and old men in wet wool."

This Fragrantica review made me chuckle because it's so true. Dublin did smell like that back in the day. I have memories of the city in 1991, about seven years before the Celtic Tiger transformed the country and eroded much of Ireland’s old-world charm. Back then, it felt like a scene out of an indie film, full of smoky pubs, police on horseback, and the occasional attractive woman striding along cobblestone streets, braless under her knit sweater. Perhaps not the most ideal setting for a young boy, but it had its moments. And yes, the earthy stink of farmers in wool suits was everywhere.

Replica When the Rain Stops doesn’t capture any semblance of Dublin, but it does smell like a blend of one part Neutrogena's Rainbath and three parts early-90s aquatic musk, a slightly gummy freshness, but without the usual overdoses of dihydromyrcenol and Calone 1951. It’s clean and sexy in its way, though not particularly original. If I’m being blunt, it could easily pass for a fabric softener. The powdery fougère undertone of the Rainbath angle adds an unusual snowy softness, further emphasized by the surprising potency of this fragrance. Just one spray lasts a solid nine hours.

The masculine opening of pink pepper and cardamom lends WtRS a spicy, aftershave-like feel, faintly reminiscent of Hai Karate or Pinaud Clubman. But soon, pale florals—mostly lily of the valley and Hedione HC—take over, shifting the fragrance toward a watery herbal vibe, supported by the faintest hint of powder. There’s a touch of Kenzo Pour Homme in how this develops, but the resemblance doesn’t linger. In the end, I like this fragrance and would use it occasionally if I owned a bottle. But for the price they're asking? No way.

11/2/24

Is Brut the Ship of Theseus?

The Paradox of the Ship of Theseus is an age-old dilemma: can an object that has had every one of its parts systematically replaced over the years still be considered the same as it was in its original form? Can an object remain essentially unchanged despite efforts at preservation to remedy its decaying components, or is it preferable to simply reconstitute the object from the decaying pieces themselves?

This question lies at the heart of the Ship of Theseus, which boasted thirty oars and was celebrated by the Greeks as worthy of preservation. After many years, every plank, every oar, every board, warp, and mast had been replaced with ostensibly identical new parts. The vessel was granted a hero's memorial, yet philosophers debated whether this act preserved the ship or merely replaced it. Was the pristine vessel purportedly used by Theseus still truly his ship after 150 years of plucking and replacing, or had it transformed into something entirely different?

This riddle invites contemplation of whether an object is defined by its material composition or if its identity transcends the materials that constitute it. Is the preserved assembly of planks and boards the true ship of Theseus, or is it the ship constructed by a bored dockworker using all the original parts, even if it appears altogether different?

I often find myself pondering this question in relation to Brut. Of all the fragrances in my collection, Brut inhabits a strange, eerie realm reminiscent of this timeless Greek paradox. Launched in 1964 as a classic fougère with a nitromusk base, Brut has undergone countless efforts at "preservation" due to changing ownership, reformulations, and evolving standards in perfumery. In 2024, sixty years after its debut, and now manufactured by High Ridge Brands, one might encounter Brut on grocery store shelves and wonder: is this really Brut?

The dilemma arises from Brut’s myriad iterations, applications, concentrations, and bottlings, surviving only by the skin of its teeth into the twenty-first century as an anachronistic homage to its era. When a young man discovers a green plastic bottle today, he might question whether this fragrance resembles the original. If he is a pessimist, he may assume it does not. Should he buy and wear it, can he genuinely feel as though he is donning Brut? What else could it be if not the product advertised on the label?

This conundrum extends to the fragrance community at large, where reformulations are ubiquitous across nearly every fragrance older than a couple of years. Even “newer” fragrances, still commercially popular, are likely to undergo minor tweaks and adjustments driven by the availability of materials and fluctuating prices. Consider Creed's Silver Mountain Water, a fragrance celebrating its thirtieth anniversary next year. Despite the passage of decades and two changes of ownership since 2020, the white bottle with a silver cap still contains something called Silver Mountain Water. However, the dense, mineralic ambergris of the original has vanished, replaced by an intensely inky version that might better serve as a flanker to its 1995 predecessor than a true representation of itself.

Fragrances evolve, yet their names and overall packaging typically remain unchanged. This invites a critical examination of older fragrances: Are you what you claim to be? After the natural oakmoss has been eliminated, after the notes that flourished in the sixties and seventies have been diminished—first slightly, then more conspicuously—are you still Brut? After the synthetics have been replaced with kinder, gentler chemicals, after the cancer-causing nitromusk molecules have been excised and substituted with other potentially harmful musk compounds, are you still Brut? The bottle bears the name "Brut," yet the scent I experience cannot possibly resemble what a man inhaled upon unscrewing the cap in 1964!

The Ship of Theseus Paradox profoundly impacts perfumery and presents a pressing question for those who cherish vintage scents and seek their analogs in the contemporary market. If we accept that constitution does not equal identity, it becomes easier to view a fragrance that claims to be a certain scent as authentically that scent, despite undergoing extensive refurbishment.

By adopting the "Continued Identity Theory," we might consider Brut to be itself, as long as the changes it endures unfold over an extended period and do not occur all at once. Imagine if Brut had been obliterated by Fabergé shortly after its release, entirely wiped from the market with every bottle bought back and destroyed. Then, in 2024, another entity produces a powdery scent and labels it "Brut." In this case, we would recognize that this new Brut is not the old Brut but something entirely different. Conversely, the Brut that has undergone minor adjustments over six decades—enough that no original part remains—still retains its identity as Brut. It remains close enough to the original to be considered the original, still the same perfume.

My solution to the Ship of Theseus Paradox is straightforward: Brut is Brut if I accept that it is. My acceptance of the current iteration allows High Ridge Brands to successfully market it to me. Helen of Troy had so thoroughly altered Brut that the formula available between 2015 and 2021 was utterly unrecognizable to me, and thus I did not consider it a fragrance at all. I did not buy it, I did not wear it, I did not respect it. Brut was effectively discontinued, despite never leaving store shelves.

High Ridge Brands successfully restored the fragrance I recognized, delivering an impressive rendition of its original formula. Consequently, I regarded Brut as "back," even though it had technically never gone anywhere. Then HRB reformulated its reformulation, slightly diminishing the fragrance's quality, yet it still surpassed the subpar version that Helen of Troy had marketed. For now, Brut endures.

10/27/24

Book (Commodity)

Palo santo is an unusual material. While it has an appealing scent, its pure form doesn’t strike me as something that would work in a personal fragrance. Sandalwood, cedarwood, and even oud have qualities that seem harmonious with human skin, but palo santo has this odd dill-pickle edge that dominates my olfactory experience, making it difficult to picture as a wearable scent. Commodity, however, changed my perspective.

Book is a fragrance containing a palo santo note that feels approachable, and I think it smells fantastic. Interestingly, Commodity doesn’t list palo santo in its note pyramid, and for the first few hours, you might not detect it. By the third or fourth hour, though, it subtly emerges, supporting the drier, “fresh” aromatics that came before. Book strives to recreate the experience of turning a dusty page. It’s a conceptual fragrance that evokes the scent of inky, well-loved paper, and I believe it succeeds. Book smells beautiful.

Yet, it raises the question: would I want to smell like an old, dusty book? This is where the niche factor enters: fragrances like this appeal only to a small subset of aficionados who yearn for the ambiance of an antique bookshop, surrounded by shelves of calfskin and vellum. Notes almost feel irrelevant here; Book simply smells like a book. Anyone who loves books enough to want to wear their scent will find joy in it.

Harvest Mouse (Zoologist)

As it turns out, I'm not even impressed. This 2023 fragrance is by Luca Maffei of Houbigant and Jacques Fath fame, and my expectation was it would smell like something that belongs in the Pineward range, only better. Well, I was half right. It belongs in the Pineward range, only it isn't any better, and might even be a little worse. It starts out promisingly enough, with a pleasant burst of warm citrus (bergamot studded with cloves), sweetened a bit by a floral orange blossom and chamomile that eventually gets sweeter and more vanillic, to the point of feeling strident. I think it's the novel accord of "Beer Extract CO₂" that ruins it. It smells biting and sharp, malty-sour but also sweet, and it evokes the feeling you have after having one too many. I give it points for uniqueness, though.

10/22/24

Fragrantica Advertises Trump's New Fragrance, Members Lose Their Sh!t

"How the hell do I delete my account?

Then there's "SaulGoo":

"When someone's shooting at you and there are innocent people standing behind you, you stay down if you're the target. Why? Because as long as the person firing sees you, they'll keep shooting. Standing up again to pump his tiny fist for what he KNEW would be a great photo op, was an opportunity for new merch GALORE."

Or perhaps we should listen to "istvan.budda.779":

"Who is the perfumer? And 200 dollars, even Chanel doesn't charge this much and Chanel is well known for being a greedy company."

And last but not least, my favorite comment by "FiaM":

"Is it time to count the balloons yet?"

My responses to each in kind: Trixie, you don't have an account. Nice try, though. SaulGoo, to quote Janosz from Ghostbusters II: "Everything you are doing is bad. I want you to know this." To istvan.budda.779: sorry about your Chanel fail, your consolation prize is a $325 bottle of Comète. And to FiaM: don't count them before they pop, sweetie. Trump Derangement Syndrome is clearly a problem for all of you. The sad thing is, it makes you look stupid, because it makes you say stupid things that nobody really believes, or even takes seriously. Eighty million Americans support Trump. I'd wager the majority of them don't have Fragrantica accounts. Time to look in a mirror.

I don't know if these complainers are Americans, real people, or just sophisticated AI bots planted by the Chinese government, but whatever they are, they're not winning, and they still haven't realized it. Their endlessly whiny and logic-free complaints about one man, a man who cut every American's taxes and protected the border as well as he could, is exactly why he's up in the polls. It's 2016 all over again.

If people want to make the energy monster go away, they should stop spewing their aggrieved energy at him. It's the strained pearl-clutching and the endless whinging that strengthens the case against them and for him. They never learn.

10/20/24

Replica Autumn Vibes (Maison Margiela)

It seems the "wood" note of the twenties is palo santo, making oud feel like a relic of the last decade—well, not quite, but it often comes across that way. This week alone, I’ve encountered two niche fragrances featuring palo santo, neither of which officially acknowledge it. One of them, Autumn Vibes, released in 2021, is a charming woody-spicy blend with autumnal accents that wraps the wearer in a warm, cozy aura for nearly eight hours. It’s pleasant enough, and actually smells expensive.

Yet again, Maison Margiela's Replica series has me questioning how closely a fragrance can mimic a room candle before crossing a line. This one opens with an aromatic burst of cardamom and pepper, which takes on a duskier tone within five minutes thanks to coriander and nutmeg. This gourmand-like opening lasts a solid fifteen minutes, its savory tones almost edible. Then, a smoky palo santo note emerges, remarkably free of the pickle-like nuance I often associate with it, yet it dominates the pyramid, leaving little room for the other elements to shine. I might be particularly sensitive to it, but the base of cedar, labdanum, incense, and a faint juniper halo does little to restore balance.

That said, Autumn Vibes is undeniably a pleasant woody scent, just a step away from being a room fragrance. It also carries a certain autumnal sexiness, with a smoothness that hints at a mature, well-constructed scent. I can picture men in their forties and fifties wearing this to bars with their wives on Friday or Saturday nights, adding a touch of sophistication to October festivities. For that kind of vibe, though, I’d prefer something with more texture (and no palo santo), like Oud Mosaic, or even Red for Men.

10/16/24

This Fragrance Did Not Slip Out Of 'Cool' and Into 'Old-Fogey'

|

| An Original 1988 Cool Water Print Ad |

Lately, I’ve noticed a trend among YouTubers, posting about Davidoff’s Cool Water, the original 1988 release, and to be blunt, I’m not impressed. It grates on me to see so many in their twenties and thirties deem it “Old School” and “Mature.” The prevailing sentiment is that this landmark release, Davidoff’s third perfume, has become outdated and cheap, reduced to a meaningless “shower fresh” relic. The implication? No one finds it relevant anymore. Apparently, Cool Water is no longer wanted by the young.

There’s something bizarre about watching a YouTuber standing in his bedroom, pontificating on how his older brother used to wear Cool Water to death, and how he vaguely appreciates it for that reason alone, while also proclaiming it inferior to Cool Water Intense. That’s where it becomes surreal. Standing there in a baseball cap and a bro goatee, shrugging away on camera, while dismissing the single most significant perfume in the history of masculine perfumery—no competition, no close second, full stop. To simply say, “Yeah, I mean, it’s okay. I like it, but I don’t wear it,” is truly surreal.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting that everyone should love or like Cool Water. There are plenty of people who loathe the stuff, and that’s fine by me. Tell me you hate Cool Water, that you’d never dream of wearing it, and I’d shrug right along with you. I’m not all that enamored with Dior’s Fahrenheit myself, and that fragrance inhabits the same legendary neighborhood as Cool Water. If my cool indifference to Fahrenheit ruffled a fan or two, I’d completely understand. Tastes differ; life thrives on contrast.

But what really gets under my skin is when people treat Cool Water like some mere footnote in the annals of fragrance, a scent that may have been cool once but that real FragBros outgrow. They then feel entitled to go on camera and wax lyrical about how trivial it is compared to modern competitors like Sauvage or Luna Rossa. These guys sound like self-proclaimed car buffs scoffing at the Ford Model T for not being an Acura TLX. In the case of Cool Water, a more fitting analogy might be swapping out the Model T for a Buick Grand National and whining that it’s no Tesla.

You don’t hold up a bottle of Cool Water and say, “This just smells played out now,” and expect that to slide. No, Cool Water is anything but played out. It single-handedly redirected the trajectory of the entire perfume industry, and it did so when the trajectory was so deeply entrenched that no one imagined it could change. Cool Water is the work of a perfumer who submitted a rough draft to an obscure niche house, which then made it their masculine flagship, which is now hailed as a masterpiece in its own right. Cool Water is the refined realization of that original masterpiece, the ultimate manifestation of Pierre Bourdon’s vision, the scent that, even today, he still ponders and savors. It is the perfect aromatic fougère. It is the only truly "modern" fougère in my collection.

Now, I’m not blind to reality. Times change, and older fragrances inevitably get labeled as just that: old. I can even admit that Green Irish Tweed, once the scent of cutting-edge modernity, now carries a whiff of the eighties. And yes, Cool Water has its ties to the shopping mall. I live in the real world; I understand. I have my own associations, remembering friends and family wearing it, myself as a teenager not quite grasping its appeal. It took me years to come around.

But as 2024 draws to a close, I can look at Cool Water and recognize that true greatness doesn’t fade with time. Its pristine design endures. Cool Water’s brilliance sparkles undimmed, a glimmering abalone in a sea of limpets.

10/14/24

Hummingbird (Zoologist)

Shelley Waddington of En Voyage Perfumes is the nose behind this 2015 creation. To date, only Squid rivals it as the Zoologist fragrance that required a full body scrub—and a shirt hurled straight into the washing machine. Here's the twist: I actually like it. This is a niche reimagining of Joop! Homme, that iconic Bourdon fragrance with the pink juice and purple box. As such, it fascinates me, answering a question I didn’t know I had: what would Joop! smell like, all dressed up in luxe materials and compositionally refined?

The answer is Hummingbird. Joop! Homme is intensely floral, but in a particular way—super sweet, heavy, yet somehow evocative of delicate petals. That buoyant sweetness, I realized, comes primarily from lilac, mimosa, and heliotrope, all crammed together into an unfocused 8-bit version of a spring bouquet. In Hummingbird, those notes are far more distinct, with greater textural finesse. Every flower stands out, yet works harmoniously to create that unmistakable magenta sweetness. The lilac is especially bright and clear, nestled with rose, a honeysuckle reconstruction, a few grams of heliotropin, mimosa that actually smells alive, and warm ylang-ylang, all cushioned atop a thermonuclear musk accord powerful enough to rival national defense systems.

As lovely as it smells, like Joop!, it’s simply too strong. So strong that neither my girlfriend nor I could tolerate it for long. The moment we got home, I jumped in the shower. Even after a vigorous scrub with Irish Spring, the fragrance clung to my skin. I’m convinced it has a half-life of eleven thousand years after just a tiny spritz on clothing—and half that on skin. If you love sweet florals and don’t mind that the rest of the block might have mixed feelings, go for it. Otherwise, for the love of all things, proceed with caution.

10/11/24

Mercedes-Benz Intense (INCC Group/Mercedes-Benz) and A Question: Should We Summarily Dismiss Fragrance SAs?

I don't want to rattle on at length about this, so I'll cut to the review and then drop in my rhetorical questions, accompanied by a personal anecdote. Mercedes-Benz is a car manufacturer. Want a luxury car of German origin? Mercedes is an option. It wouldn't be my choice, but I can see why people like them. Most are stylish, fast, comfortable, and undeniably a status symbol, at least in the U.S. Sure, their luxury cache has dwindled in the last twenty years with stuff like their A Class and C Class "Kompressor" sedans, but they still speak to the quasi-wealthy among us.

Sadly (for Mercedes), the cars weren't enough to boost their self-image, and at some point they turned to contracting out their own signature perfume line, with a surprising number of fragrances, most of them rack store bargain-basement offerings that cut against whatever exclusive vibe the Mercedes fanclub of testosterone-kompressed men are after. It's sort of like what happened to Montblanc; go from selling $4,000 pens to $40 perfumes, and eventually you start questioning the pens more than the perfumes. If I were Mercedes, I'd scale back on the number of frags on offer, limiting it to one or two, and focus more on the cars, but what do I know? Apparently their Burlington Blitzkrieg strategy works for them, so I guess they should keep on rolling. Enter Mercedes-Benz Intense for Men.

Released in 2013 as a follow up to the original of the same (sans Intense) name, the brief is crystal clear: Do Fahrenheit, but closer to the Aqua version, with a shot of "New Car Smell" somewhere in with the gassy violets and grassy vetiver. If you want Fahrenheit with the petrol dialed down a notch and the marine-ambergris element of its flanker tuned-up in the base, this is a no-brainer fragrance to own. It's not quite as complex in its florals, but it doesn't smell "cheap" in comparison to its template, and I think it's close enough to replace the original Dior if you're tired of shelling out a Ben per bottle. It's that good.

Now for my anecdote, still fresh in my memory. I bought this fragrance at the mall as a birthday gift for a family member. Upon entering the perfume shop, I was greeted by a polite Indian woman around my age. I asked if she had any Dior fragrances, specifically looking for a Fahrenheit flanker. She directed me to the Dior section—no flankers in sight, just the usual suspects: Fahrenheit, Sauvage, and Dior Homme. What followed was a series of obscure fragrance recommendations, one of which claimed to be an Arabian brand but was made in New Jersey. Needless to say, it didn’t smell like Fahrenheit, or even Sauvage, for that matter. Then, she pitched me an Israeli brand claiming London heritage that bore no resemblance to anything by Dior. I really didn't feel like playing this game, so I pulled up Fragrantica on my phone, hoping it would steer me toward a better option.

This was a big mistake. She quickly got rude with me, borderline insulting. I showed her the Fahrenheit page as it loaded and asked if she knew the site, and she said, "No, why would I look at that? Yes, I see, there's Fahrenheit. So what?" I then explained that they have a feature where fragrances are compared by votes, and pointed to the first thing that showed up: Mercedes-Benz Intense. She didn't say anything at first, as if processing that I was ignoring her useless suggestions in favor of the almighty internet, and I wondered if she was going to kick me out of the store. Instead she visibly gathered herself and said, "Yes, I see Mercedes-Benz there, we have that one." She beelined across the store for it, with me in tow. She sprayed it on a strip, still looking pissed, and I took a sniff. Bingo!

Two minutes later, I was out the door with the fragrance, and not a word passed between us. The truth is, we had both gotten under each other’s skin. In hindsight, I can see that I may have been a bit dismissive. I asked for her help, entertained a couple of suggestions, and then promptly pivoted to my own internet search. Honestly, that might have annoyed me too, had I been in her shoes. But listen, I tried to be friendly. I asked if she was familiar with the site I was using, I kindly showed her what I was doing as I navigated it, and even spared her the hassle of rummaging through countless bottles to find what I was after. What's the beef?

It makes me wonder if we should just skip the friendly sales interactions altogether and get straight to the point: "Give me [x]." I don’t need to smell a dozen knockoff brands no one’s heard of, and frankly, I don’t care that your feelings might be hurt because I’m bypassing your advice. Your suggestions are awful. Your store is fantastic, but your role in it? Not so much. If you’re going to be that consistently bad at your job, then yes, I’ll happily and summarily dismiss you, no questions asked. Real talk.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)