12/26/21

Eau de Minthé (Diptyque)

12/23/21

Lemon, Cedar, Amber (Pecksniff's)

12/19/21

Alcolado Glacial (Curacao Laboratories Ltd.)

12/17/21

Florida Water (Lanman & Kemp Barclay)

12/12/21

Polo Ultra Blue (Ralph Lauren)

|

"I'll take a pack of Ultra Blues, please." |

12/6/21

Ombré Leather (Tom Ford)

12/4/21

Vanilla (Alyssa Ashley)

12/1/21

Denim Black EDT (Bellevue Parfums)

11/25/21

Master Witch Hazel (Master Well Comb)

11/20/21

Candie's Men (Iconix Brand Group)

|

| A Candie's Shoe Ad from the 1990s |

11/6/21

Joy (Jean Patou)

9/20/21

Clubman Country Club Shampoo (Pinaud)

9/1/21

Stephan Lilac Fragrant Skin Toner (Stephan)

8/21/21

17 Oud Mosaic (Banana Republic)

8/8/21

Eau de Quinine (Pinaud)

|

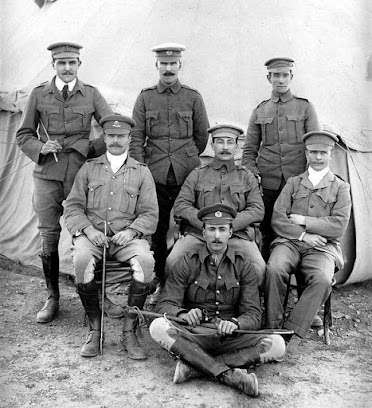

British Colonial Soldiers, early 1900s |

8/1/21

Let's Keep the Terms "Designer" and "Niche"

"You have to ask why someone would buy something. With 'designer' fragrances, people are buying because they want a connection to the designer brand, and the product is sold to them via the perceived pedigree of that brand. With 'niche' there's no prevailing brand awareness to form the cultural tailwinds because the brand is entirely conceptual. Unlike a Chanel, where I can associate the perfume with the clothing and accessories (and commercial image), a Xerjoff stands alone with only the Xerjoff name and perfumes to speak for it.

If I don't understand something specific about Xerjoff perfumes, like what kind of fragrances they make, and how those fragrances compare to everything else, I won't be inclined to bother buying anything. Thus I'm basing a purchase solely off of what I know, rather than what I perceive. This makes the act of buying one of self-stratification with niche, while buying designer is me adhering to commercial stratification; when I buy Xerjoff, I am distinguishing myself as someone who appreciates Xerjoff perfumes, whereas a Chanel purchase is Chanel successfully tagging me a Chanel customer.

The problem with your term 'boutique' is that it's a distinction without a difference. Chanel boutiques are literally what they're called. So does that make Chanel's frags 'boutique' frags, when they're clearly just 'mainstream,' as you say? Creed Boutique is another example. Creed's logo is a clothing tailor's scissors. They're not hiding the ball there, they're telling the world they're designers . . . These terms 'boutique' and 'mainstream' don't really address what customers are buying, because they negate why they're buying them. So basically let's just keep 'niche' and 'designer.'"

While I think his argument is interesting, my counter-argument is that there's really no point in trying to separate the two categories with different language when the current language is clarifying from a consumer's point of view. Terms like "boutique" and "mainstream" are probably useful guidance for the suits wanting to know which market they should penetrate, but they fail to acknowledge the psychological motivation of the customer. Daver actually mentions this, stating that "niche" used to target a specific audience, which elaborates on the exact definition of the term, yet he deviates into the notion that the targets have broadened enough to warrant calling the whole mess "boutique." Certainly you could do this, but it would confuse many people as a colloquial term, especially when discussing designer boutiques. There's just too much definitional overlap there, a certain Comedy of Semantics.

He argues that there's too much audience overlap between the two market segments, but by taking an introspective approach to that argument, I hoped to parse out the utility of maintaining the Old Guard terms. In some ways I see his point more in regards to saying "mainstream fragrance," simply because this doesn't confuse. Stuff like Bleu de Chanel and Dior Homme are "mainstream" and mass-market. But there's still a linguistic weakness inherent to applying this label; we live in a world where familiarity isn't always the act of knowing. While Chanel and Dior are familiar "mainstream" brands, there are entire swaths of their catalog that exist under the radar. Everybody knows Chanel No. 5, but a tiny subset of everybody knows of Chanel Boy. Yet the same "mainstream" brand makes both. If you're releasing perfumes that very few people are aware of, are you in the "mainstream," or simply successful at penetrating mainstream markets? How would a customer ever discover Boy? Oh, yes, because they're interested in something to go with a Chanel tweed sweater, and the knowledgeable salesman happens to mention lavender. Suddenly the clothing matters again, even if it has nothing to do with how anything smells. Clark's Glasses vs. Superman's Cape.

If you ask me, "What kind of boutique fragrances do you like," my answer will be, "Huh?" Ask me "What niche brands are in your collection," and I'll immediately know what you're talking about, because I'm the niche audience that wanted specific items in my collection. Boutique fragrances are pretty much all fragrances, and it's hard to know what you're after if you use that word.

We need to be clearer in the language we use. In a time where everyone has their own pronouns and "truths," where definitions are being adjusted and expanded upon on a minute-by-minute basis, it would behoove us to rope in meaning when we see it, and I'm fairly certain the demarcation of perfumery markets is a worthy subject for that. Then again, Super-ego Superman would probably reduce me to a blubbering mess for suggesting it, so let's keep this between us.

7/16/21

Salvatore Ferragamo Pour Homme and Yet Another Irrefutably Clear-Cut Account of In-Bottle Maceration

"I must say, my bottle has matured spectacularly well over the past 5+ years. When I first got it I enjoyed it but had a distinct impression it was a bit watered down and I could spray the entire bottle on without sending people running. In the mean time it would seem to have concentrated but the bottle doesn't appear to have seen the juice contract that much. It's become stronger obviously, but also a bit sweeter and I can definitely detect many more notes than when I first got it."

When this person states that the bottle "doesn't appear to have seen the juice contract," he's referring to the chance of some liquid volume reduction due to alcohol evaporation, which would lead to oil concentration and a stronger perfume. I've had this happen with several retail-purchased Creed GITs and Orange Spice. Initial perceptions of GIT is it's weak and transparent in nature for the first few wears, at which point I'll put it away for a while. When I return, it's a completely different story. I recall one bottle starting out like water, and a few months later it had grown so potent it was almost unwearable (and had reached a Joop! Homme strength). Orange Spice also changed, going from a few thin hours to double shifts of pounding Valencias within five years. I've since then witnessed dozens of people commenting on the same thing happening to them.

It's intriguing that Ferragamo's scent is cited as one that undergoes in-bottle maceration after first use. My take on my new bottle is that it's pretty potent for two hours, and then dies down to roughly less than half its original strength. This behavior is aligned with the behavior of other fragrances that kept macerating while in my possession. I wouldn't be the least bit surprised if it developed into a different performer over the next year or two, and I will keep you updated on that.

7/1/21

CK One (Calvin Klein)

|

| Beautiful Ad, Beautiful Frag |

6/22/21

Post-Pandemic Update: Stuff I've Been Into

|

| My Chinese knock-off of a brass Victorian mantle clock, cherub intact |

6/12/21

Club de Nuit Milestone (Armaf)

|

| Eat your heart out, Laurice. |

6/1/21

Tribute Cologne for Men (Avon)

|

The sticker on the bottom of my 1976 Liberty Bell-shaped bottle |