|

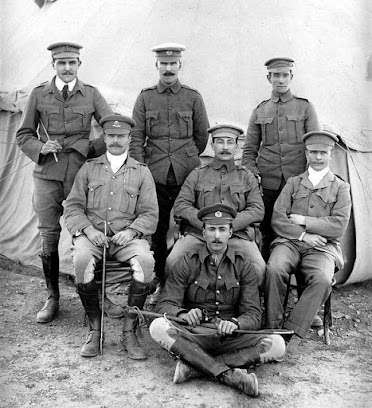

British Colonial Soldiers, early 1900s |

I'd like to get this out of the way first: Pinaud's hair tonics are not meant to provide hold. Compare the ingredients to their aftershaves, and you'll find the hair tonics are merely alcohol, fragrance, preservatives, and artificial color. The only difference is it says Hair Tonic instead of Aftershave on the label. Hair tonics are meant to de-flake the scalp and soften the roots for healthier hair, and that's it. Use styling gel to mould your coif, but be sure to run some Eau de Quinine through first to clean your head.

Pinaud's Eau de Quinine is the brand's oldest surviving barbershop product. According to the Smithsonian, it was originally released in the 1850s, and has survived nearly two centuries in various iterations. Today it is labeled for hair-care but easily doubles as an aftershave-cologne, and I find its scent to be one of the most durable in the Pinaud lineup, a lovely shaving foam tune with a bracing quinine and cherry chord instead of anisic lavender, followed by a minuet of patchouli and vanilla in the dry-down.

People ask, why Eau de Quinine? What place does quinine have in a barbershop? The answer takes us back to nineteenth century England, when Britain's Imperial Century saw the expansion of its empire across Africa and Asia, continents where malaria was everywhere. The Brits knew quinine was useful in fighting mosquito-borne diseases, and put it in anything they could - water, tablets, alcohol, toiletries - and it became an essential tool in the belt of the English colonizer. Pinaud marketed their Eau de Quinine shampoo, hair tonic, and cologne to safari-bound parties, and it caught on in the 1870s, when expansion was fully underway, becoming popular as hair-care for women, and an all-over bug repellant for men. This required copious amounts of quinine extract from the bark of the South American and Caribbean cinchona tree.

Synthesis of quinine was first achieved in 1944 by organic chemist Robert Woodward and Professor William Doering, and Pinaud's hair tonic made a comeback around that time, although natural quinine retained its status. Ian Fleming featured Pinaud's Eau de Quinine shampoo in chapter two of the 1963 novel On Her Majesty's Secret Service, detailing how a road-weary James Bond found hotel respite in a bottle of champagne and a cold shower using "Pinaud Elixir, that prince among shampoos." I find this interesting because it shows that Fleming himself used the shampoo, and held it in high regard. He likely booster-shot new life into Pinaud's product line, although sadly the shampoo has long been discontinued. Bring it back, Pinaud.

Today, Eau de Quinine remains a historical novelty, but I think it's amazing that Pinaud sticks to its guns and continues making it. I wouldn't recommend it as a hair product, but heartily endorse using it as an aftershave and cologne. I get several hours of noticeable longevity from it, and find the smell very much in line with traditional barbershop tonics. It has a freshness, yet also a smokiness, a hint of tobacco, a subtle earthiness, and a masculine vanilla powder at the end that is tooled finely enough to compete with pricier fare. It gets mixed reviews, with one notable blogger calling it "utterly boring and uninspired." I disagree - this is historically inspired, and thus unavoidably interesting.

A note on unicorn vintage hunting: for several years now some jerk has been listing a 30 oz bottle of 1960s Elixir shampoo on eBay for $1k. So far, no buyers. Let's keep it that way. Vintage Pinaud is best priced between fifty and a hundred dollars, unless the bottle is from the eighteen-hundreds, pristine, sealed, and full.